It’s not an intentional campus secret, but, if you ask someone at Elizabethtown College to direct you to the cadaver lab you’ll likely get a blank stare. It’s an area of campus not well-traveled.

It’s not an intentional campus secret, but, if you ask someone at Elizabethtown College to direct you to the cadaver lab you’ll likely get a blank stare. It’s an area of campus not well-traveled.

Housed in the Department of Biology and primarily used by anatomy and physiology classes to learn about bodily systems, there are at least two cadavers on campus in any given semester.

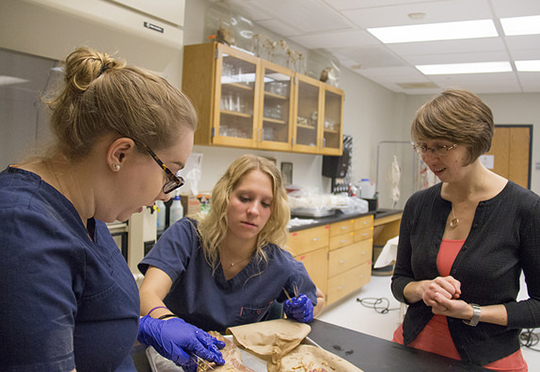

Photographs in anatomy textbooks are acceptable learning tools, said Anya Goldina, assistant professor of Biology, but working directly with real body is eye opening. “To actually see the same muscle that you saw in a textbook on the cadaver, that is when the information clicks in. It’s automatically retained. Students won’t forget.”

Traditionally, the first time pre-med and physical therapy students have cadaver experience is in medical or graduate school, Goldina said. For nursing and occupational therapy students in other programs, working with cadavers is a very rare opportunity, entirely. “It’s uncommon for undergraduates in a college of our size to have a cadaver lab,” she said. “Typically students will learn from pictures and plastic models.”

It’s uncommon for undergraduates in a college of our size to have a cadaver lab.”

E-town grads realize and appreciate their advanced opportunity in medical school when fellow students are having their first cadaver experience. “A lot of our students comment on how well-prepared they felt coming out of our program,” Goldina said.

E-town grads realize and appreciate their advanced opportunity in medical school when fellow students are having their first cadaver experience. “A lot of our students comment on how well-prepared they felt coming out of our program,” Goldina said.

Danielle Barattini, a fifth-year E-town occupational therapy student and teaching assistant in anatomy and physiology  classes, refers to the cadavers as “amazing teaching tools.”

classes, refers to the cadavers as “amazing teaching tools.”

Barattini said she became interested in human anatomy when she visited an exhibit of plasticized models. “I wasn’t completely shocked,” she said. “At first I was uncomfortable, but then I thought ‘wow; this is inside my body’.

“For OT, it’s important to know placement of muscles,” she said, noting that students need to know how stroke or spinal cord injuries affect the body. “You can see exactly what each muscle does in the body.”

Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center supplies the cadavers to the College through a special agreement. “It’s a generous gift that the person donated to science,” Goldina said of cadaver donors’ last wishes.

Before sending them to the College, Hershey Medical Center uses an embalming solution to preserve the cadavers and keep them from decomposing. The College keeps the cadavers viable for study and dissection for up to three years, storing them in a temperature-controlled facility. Contrary to popular belief, Goldina said, the bodies are not frozen. Lower temperatures can damage the tissue, distorting educational opportunities.

Though student assistants and those who teach anatomy have direct access to the cadavers, anyone with an interest can arrange a visit, Goldina said. “It’s not meant to be exclusive.” Local high school students interested in forensics have toured the lab.

“Students at E-town have incredible opportunities to expand their knowledge of anatomy. For students who do well in anatomy and physiology, we provide the opportunity to become teaching assistants for the course or work as dissecting assistants, helping prepare the cadavers for incoming students.”

When Marlee Schwalm, a senior biology major, was hired this past August as a dissection assistant, her first order of business was to expose muscle groups and bone.

“We tease the skin away from the connective tissue, maintaining the muscles,” said Schwalm, who aims to be a physician’s assistant. “Each cadaver is so interesting,” she said, noting this semester’s female body had no abdominal muscles on one side. “She must have had surgery and had them removed.”

Though she has been alone in the lab with the cadavers, Schwalm said she is not uncomfortable. “It’s not like a horror movie,” she quipped.

Most students are unsure of how they will feel when they first enter the cadaver lab, often associating the death as a negative and painful experience. But, Goldina said, it quickly becomes a balancing act when they understand how beneficial the cadaver work can be. They are sensitive and respectful, seeing the death with dignity and understanding the importance of the cadaver donation.

“My first exposure to the cadavers was as a human anatomy and physiology student,” said Sara Bates, a biology-allied health major. “Opportunities to observe and touch the cadavers are highly integrated into the A&P courses. These opportunities supplement a student’s learning of individual muscles (their locations and functions), as well as how groups of muscles are arranged and function together in the body.”

When her course was completed, Bates was asked to assist in dissecting the new cadavers for this year’s A&P classes. It is rare for undergraduate students, to dissect cadavers themselves, she said. “Cadaver dissection is usually reserved for professors and graduate students in medical programs. I’m very grateful to have been able to participate intimately in dissection with another undergraduate student and our professor, Dr. Anya Goldina.”

Once the cadavers have been studied and analyzed by the students and professors, the College returns them to Hershey so families may put the donors to rest and celebrate their lives. If, however, the men or women do not have living family members, Penn State Hershey conducts its own celebration of life.

“I can’t stress enough how much we appreciate and learn from this generous gift from the person, from their families,” said Goldina.

“These cadavers,” she said, “are an amazing asset to the anatomy and physiology education at E-town; they help us prepare our students for the next step in their careers, making them more competitive.”