When we spend a good deal of time with another person, we begin speaking similarly and picking up mannerisms. But as Debra Wohl, professor of biology at Elizabethtown College, and Megan Mendenhall ’16 found out, that’s not all we pick up.

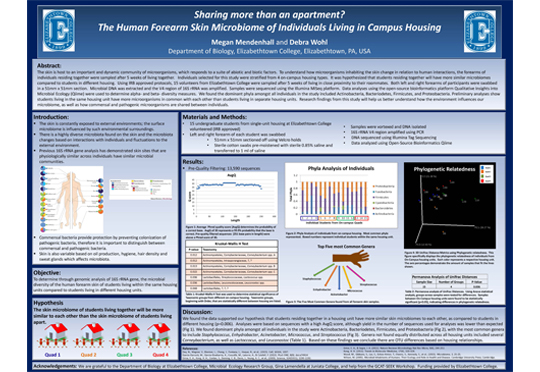

The two recently presented “Sharing more than an apartment? The Human Forearm Skin Microbiome of Individuals Living in Campus Housing” at an international conference for ecology. Their study examined the skin microbiome of students living together over a period of five weeks in on-campus housing.

“When you spend time together it does affect your skin microflora,” Wohl said, referring to collective bacteria and other microorganisms. Similarly, when roommates separate over a five-day break, their skin microbes differ.

The study of human microbiomes is fairly new, Mendenhall said. A big area of research, according to Wohl, is the microbial cloud. “If you knew what your microbial cloud looked like or the microbes that cover the inside and outside of you, we might be able to predict diseases or prevent particular diseases from occurring,” she said.

… we might be able to predict diseases or prevent particular diseases from occurring.”

Wohl said the community composition and diversity of microorganisms associated with each individual make up a pattern. She and Mendenhall hypothesized that they’d be able to sample a person and, based on the patterns, determine to which group (i.e. housing unit) they belonged. Their data supported this hypothesis. They found, though, that after individuals were apart for an academic break, there are enough differences in microorganisms associated with the skin to form an unclear pattern, making it difficult to determine to which group an individual belongs.

As a student enrolled in a year of research, Mendenhall followed her project from start to finish. Formulating the research question to presentation of the findings is unique for a research project done on this timeline. “Often you jump in (to a project) when someone’s already started, or you start it and somebody else finishes it,” Wohl said.

This study arose from another exploratory project done two years ago when one of Wohl’s students, interested in microorganisms, sampled other students’ arms before and after a biology lab to determine if the microorganisms looked like those on the lab benches, on their lab partners or remained as they did upon arrival.

Mendenhall’s project took a different approach, by choosing to sample students who spend a larger amount of time together.

“We thought if you lived together for so long you’d probably look a lot like your roommates, and we found you only look somewhat like them,” Wohl said, referring to the microorganism patterns.

While this was a collaborative project, it was driven by Mendenhall, Wohl said. “We bounced ideas back and forth all the time and sort of fleshed out the questions,” she said. Though she helped Mendenhall analyze the data, the student devised the idea of sampling the College’s Schreiber Quadrangle residents, swabbing everyone’s arms and taking on the challenge of catching students as they arrived back on campus from Fall Break, prior to seeing their roommates.

Mendenhall initially presented their findings at the College’s 2016 Scholarship and Creative Arts Day. Then, she and Wohl reanalyzed the data prior to presenting at the conference. They focused on the microbes during the five-week period roommates spent together.

“It was, for me, personally, very fun and satisfying to go to a conference with Megan,” Wohl said. “She was great to work with [and very] disciplined.”